Abstract

This paper proposes a design and control approach to parallel resonant converter (PRC) based battery chargers. The proposed approach is particularly suitable for the constant-current constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging method, which is the most commonly utilized one. Since the PRC is operated at two different frequencies for each CC and CV charging modes, this approach eliminates the need for complicated control techniques such as the frequency-control and phase-shift-control. The proposed method not only simplifies the design and implementation processes of the converter unit but also simplifies the design of output filter configuration and decreases the number of the required components for the control of the charger. The proposed method is confirmed by two experimental setups. The results show that the designed charger circuit ensured a very stable constant current in CC charging phase, where the charging current is fixed to 1.75 A. Although a voltage increase in CV phase is observed, the charger circuit is able to decrease the charging current to 0.5 A in CV phase, as depicted in battery data-sheet. The efficiency of the charger is figured out to be in the range of 86%-93% in the first setup, while it is found to be in the range of 78%-88% in the second setup, where a high frequency transformer is employed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The extensive use of batteries in small- to large-scale power systems, such as cell phones, plug-in and hybrid electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy systems (RESs), require convenient charger circuits. The basic expectations from these circuits are that the power electronic unit has high power density and operates at high efficiencies, while they are able to keep up with the dynamic behavior of the battery pack [1].

Although there are various charging algorithms, the constant-current constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging is the most common method that is utilized for the charging process of various battery types [2, 3]. The CC-CV charging algorithm is comprised of two charging modes. In the first mode, the charger circuit provides a constant current until voltage of the battery pack reaches to a certain value. Beyond this point, the charger circuit supplies a constant voltage output, while the charging current slowly decreases.

The resonant converters offer several advantages such as lower switching losses leading to higher switching frequencies and higher power densities [4,5,6]. Thus, resonant converters are the key technology in DC power applications [1]. Consequently, many resonant converter topologies have been widely used as battery chargers, especially for EVs [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Resonant converters are categorized into three basic topologies, depending on the manner by which resonant tank type the energy is extracted from. These are the series resonant converter (SRC), parallel resonant converter (PRC), and series-parallel converter (SPRC) [1, 6]. PRCs exhibit some desired features; easy output voltage regulation for above the resonance frequency operation at no load, less conduction losses, wide load variation (load insensitivity) and decreased ripple of the output voltage. Moreover, PRCs inherently ensure protection against short circuit conditions and have capability of no load operation, with the exception of near resonance frequencies. One major drawback of the PRC is that the output voltage of the converter is highly dependent on the load and therefore it can be increased to very high values under no load [4, 14]. Considering the facts mentioned above, PRCs seem to be one of the convenient topologies for battery charger applications.

The operation of PRC is well-known [15] and the most basic approach for output voltage/current regulation is the frequency control method. A number of PRC configurations with frequency control for battery applications have been reported in the literature. Reference [4] offered a PRC topology for the mobile battery charger applications, in which the large output side inductor have been replaced by a relatively small sized inductor. An alternative full bridge PRC for RES has been suggested, where the resonant tank elements have been connected in a different configuration in order to decrease the voltage stress on the semiconductor devices in [16]. In [17], a PRC topology for the grid-connected RES with reduced switching frequency variations has been demonstrated. A recent study [18] compares four basic frequency-controlled resonant converter topologies operating above the resonance in the aspect of being applicable as on-board EV chargers based on CC-CV charging method. Their study states that the PRC performs well in CC charging mode, whereas it has very low efficiency in the CV charging mode. This is caused by the fact that, at above resonance operation, the input current does not significantly decrease as the load decreases [18]. Although the frequency-control method is commonly applied, the main problem with this method is that the switching frequency must be adjusted in a wide range. This complicates the design and optimization of circuit elements. In addition, the change of switching frequency is actually quite sharp so that it causes more switching losses and consequently a decrease in the general system efficiency [19,20,21].

In the literature, several approaches have been proposed for avoiding the frequency control. One of the earliest approaches is the phase modulated resonant converters (PMRC) that was published in the late 80’s. In [22], a constant frequency resonant converter is designed by implementing two conventional SRC or PRC whose outputs are connected either in parallel or in series. These converters are operated at a constant frequency, whereas the output voltage is controlled by the phase displacement at the inverter stages. The disadvantages of PMRCs are the unbalanced inductor currents and capacitor voltages at the resonant tanks. Moreover, the circulating currents at light loads and high component stresses are some of the major drawbacks [23]. In [24], clamped mode resonant converters (CMRC) have been proposed. These converters regulate the output voltage by controlling the pulse width of square voltage across the resonant tank. The major disadvantage of these type of converters lies in the fact that each couple of switching elements have different peak and RMS currents. A further approach is proposed in [19], where the output voltage can be regulated by the utilization of a variable inductor in the resonant tank. The shortcoming of this approach is the low efficiency due to the operation at far from the resonance frequency. A classical type PRC operating as a constant current source at resonance frequency has been reported in [25]. Reference [26] offers another technique by employing a switched capacitor at the resonant tank for controlling the output voltage gain. A recent approach proposed by [27], is a pulse-width modulation (PWM) operated secondary resonant tank (SRT) converter, which is comprised of a conventional full-bridge PWM inverter and a resonant tank connected at the secondary side of the transformer. The voltage/current regulation is achieved by the closed-loop control of the PWM generator.

As reviewed above, there are several methods for achieving voltage and current regulation for resonant converters. The most commonly utilized technique, the frequency control method, suffers from the efficiency drop caused by the sharp changes of the switching frequencies. Moreover, the design process is more complicated since the switching frequency is not constant. Furthermore, it is also worth mentioning that the output voltage regulation of resonant converters are claimed to be challenging. The major reasons for this issue are the load variations, the discontinuous and highly non-linear converter models and immeasurable state variables. Similar problems also exhibit challenges in different engineering disciplines that can be overcome with complicated techniques [28]. Thus, even adaptive controllers for resonant converters have been proposed in [29, 30].

As mentioned previously, there are several proposed methods for avoiding the frequency-control technique, such as PMRCs, CMRCs etc. However all of these techniques suffer either from unbalanced currents, decreased efficiencies or complex circuitry. Moreover, all of these techniques require closed-loop controllers for CC and CV phases. In contrast to reviewed techniques, the proposed approach in this paper utilizes two distinct inherent features of the PRC for achieving current and voltage regulation under CC-CV charging method. In this study, which is a more comprehensive and extended version of [31], the PRC is operated under two different constant frequencies for each charging phase, either as a constant current source (CCS) or a constant voltage source (CVS). The proposed battery charger does not require any complicated circuitry nor complex control approaches. Moreover, this approach diminishes the need for closed-loop current / voltage controllers, when the input voltage stability is assured. Thus, the design of power electronic unit and implementation process are simplified. What is more, the method offered in this paper eliminates the disadvantage of the PRC, mentioned in [18], by operating the PRC below resonance.

2 Theoretical background

Bucher et al. have investigated the steady-state characteristics of the PRC analyzed by several different approaches. They stated that three different types of solution approach exist; exact time domain solutions, first harmonic approximation (FHA), and extended first harmonic approximation (e-FHA). Their study claimed the solutions derived by the exact time domain analysis to be very accurate. On the other hand, the FHA assumes that the inductor current and capacitor voltage is sinusoidal, leading to inaccurate results for some operation modes. However, the e-FHA assumes that only the inductor current is sinusoidal. Both FHA and e-FHA results are acceptable for switching frequencies above the resonance, whereas the results of the FHA are not accurate for discontinuous conduction mode (DCM) conditions [32]. In this study, the exact solutions of the PRC using state plane analysis (SPA) is investigated and briefly summarized. The analysis summarized here is for the full-bridge PRC topology including a transformer with a turns-ratio of \(n=1\). The details of the SPA can be found in [33, 34].

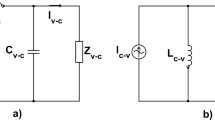

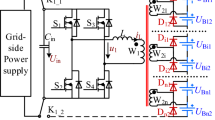

The full-bridge configuration of the PRC is illustrated in Fig. 1 . This circuit can be represented in a simpler form as shown in Fig. 2. Please note that, the terminal voltage \(V_T\) and terminal current \(I_T\) are square-waves with a magnitudes of \(\pm V_g\) and \(\pm I\).

The mathematical expressions derived for the equivalent circuit are:

Now, the circuit parameters are normalized using the base values given in Table 1.

The state equations in normalized form become:

where \(w_{0}\) is the angular resonance frequency; \(M_{T}\) and \(J_{T}\) are normalized terminal voltage and terminal current values. The solutions of these differential equations are:

Using differential geometry techniques, the relationship of two important quantities \(V_{C_r}\) and \(i_{L_r}\) can be represented geometrically as a circle centered at the point (\(m_{C_{r}}=M_{T}\), \(j_{L_{r}}=J_{T}\)), as shown in Fig. 3. The radius of the circle, r, and \(\phi\) depend on the initial conditions.

Normalized state plane trajectory for circuit in Fig. 1

2.1 Operation modes

Now that a general geometrical solution for the equivalent circuit is obtained, solutions for all subintervals of the circuit can also be achieved. The PRC has 4 continuous conduction mode (CCM) and 2 additional DCM subintervals, depending on the states of the \(V_{C_r}\) and \(i_{L_r}\).

2.1.1 Subinterval 1

The first subinterval of CCM, shown in Fig. 4a, occurs when the terminal voltage is \(V_{T}=+V_{g}\) and the terminal current is \(I_{T}=-I\). In this mode, S2, S3, D6, D7 conduct and the capacitor voltage is negative, \(V_{C_{r}}<0\).

2.1.2 Subinterval 2

The second subinterval of CCM, seen in Fig. 4b, occurs when the terminal voltage is \(V_{T}=+V_{g}\) and the terminal current is \(I_{T}=+I\). In this mode, S2, S3, D5, D8 conduct and the capacitor voltage is negative, \(V_{C_{r}}>0\).

2.1.3 Subinterval 3

The third subinterval of CCM, illustrated in Fig. 4c, occurs when the terminal voltage is \(V_{T}=-V_{g}\) and the terminal current is \(I_{T}=+I\). In this mode, S1, S4, D5, D8 conduct and the capacitor voltage is negative, \(V_{C_{r}}>0\).

2.1.4 Subinterval 4

The fourth subinterval of CCM, presented in Fig. 4d, occurs when the terminal voltage is \(V_{T}=-V_{g}\) and the terminal current is \(I_{T}=-I\). In this mode, S1, S4, D6, D7 conduct and the capacitor voltage is negative, \(V_{C_{r}}<0\).

2.1.5 Subinterval 5 (additional DCM Subinterval 1)

The fifth subinterval is caused by the DCM operation of the PRC under heavy load. In this case, the inductor current, \(i_{L_r}\) at the end of the first subinterval is less than the terminal output current, \(I_{T} = I\). Thus, the transition to Subinterval 2 cannot happen. Therefore Subinterval 5 occurs, where capacitor voltage, \(V_{C_{r}}=0\) and current \(i_{C_{r}}=0\) until the inductor current is charged up to \(i_{L_r} = I\). In this interval, S2, S3 and all output diodes, D5-D6-D7-D8, conduct. This mode is represented in Fig. 4e.

2.1.6 Subinterval 6 (additional DCM Subinterval 2)

The sixth subinterval is the dual of the fifth subinterval. It occurs during the transition from Subinterval 3 to Subinterval 4. In this interval, S1, S4 and all output diodes, D5-D6-D7-D8, conduct. It is illustrated in Fig. 4f.

2.2 State plane trajectories for CCM and DCM

Since geometrical solutions for all subintervals are obtained, they all can be interpreted in a single state plane trajectory plot. In the CCM case, Subintervals 1 to 4 occur, where each subinterval can be represented as a circle centered at the terminal voltage and current values. The complete state plane trajectory for the CCM is illustrated in Fig. 5.

In case of DCM operation, two more additional subintervals are observed, where the inductor current, \(i_{L_r}\) is charged up to the value of terminal output current, \(I_{T}\). The complete state plane trajectory for the DCM is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The output voltage expressions of PRC can be derived parametrically by using some averaging techniques, resulting in the expressions for CCM case given in (8)–(10).

where \(\varphi = (\beta - \alpha )/2\). As it can be noticed, the value of \(\varphi\) must be calculated for solving the normalized output voltage value. Since DCM and CCM trajectories are derived, the solutions important parameters, such as M, J, DCM boundary condition \(J_{crit}\), can be derived geometrically.

The DCM occurs for \(J>J_{crit}\), where \(J_{crit}\) is expressed as:

The equations for the DCM solution are:

Using these formulas, complete output characteristics of the PRC is obtained as illustrated in Fig. 7.

These output characteristics describe the relationship between J and M for different values of F. The solid lines represent the CCM, whereas the dashed lines represent the DCM.

3 Proposed method

3.1 Basic information on proposed method

In Fig. 7, it is seen that operation at \(F=1.0\) results in a straight output curve for \(M\ge 0.3\) boundary. This means that, within this boundary the PRC can act as a CCS with a normalized output current of \(J=1\). A second important feature is observed for operation at half resonance frequency \(F=0.5\), where the putput curve is approximately a straight vertical line for \(J\le 1.5\) boundary. Thus, it can be concluded that the PRC operates as a CVS supplying a normalized output voltage of approximately \(M\cong 1\). Considering these two distinct features, it can be inferred that the PRC can be easily designed for CC-CV charging by utilizing their inherent characteristics. Basically, the PRC is operated at resonance frequency, \(F=1.0\), for CC charging mode, while it needs to be operated at half resonance frequency, \(F=0.5\), for CV charging mode.

3.2 Designing PRC

The first step of the design procedure is to determine the maximum charging current (the constant current value in CC phase), \(I_{\text {max}}\), and the maximum charging voltage (the constant voltage value in CV phase), \(V_{\text {max}}\). In order to figure those out the data-sheet of the battery should be referred.

3.2.1 Determining resonant tank elements

In the theoretical background section a brief analysis for the full-bridge PRC topology with \(n=1\) transformer turns ratio was given. For different PRC topologies, the base voltage and base impedance values should be altered so that the previously derived SPA solutions in normalized form remain the same. Base values for common PRC topologies are given in Table 2. It should also be pointed out that if a transformer is employed, the base impedance is calculated according to the parameters of resonant tank referred to the secondary side. The parameters \(L_{r}^{''}\) and \(C_{r}^{''}\) are the values of resonant tank elements referred to the secondary side of the transformer.

In this study, a low power application example is included in the last section. Therefore, it is aimed to build a test setup with half-bridge topology in order to decrease the number of components and the cost of the charger circuit. Thus, the formulas given in this section are obtained using the base values \(V_{base}=\frac{nV_{g}}{2}\) and \(R_{base}=\sqrt{\frac{L_{r}^{''}}{C_{r}^{''}}}\). For this case the normalized output voltage is expressed by:

The maximum voltage is achieved and maintained at CV charging phase, where \(F=0.5\) and \(M=1.0\). By rearranging (16) for CV charging mode, the necessary transformer turns ratio can be obtained by (17).

Now, it is necessary to determine the values of other quantities for obtaining the desired output current at CC charging mode. The expression for normalized output current is given in (18).

The base current value is:

The maximum current, \(I_{\mathrm {max}}\), is achieved at CC charging phase, where \(F=1.0\) and \(J=1.0\). Now, the characteristic impedance for the resonant tank, \(R_{0}=\sqrt{L_{r}^{''}/C_{r}^{''}}\), can be calculated.

Using (21) the value of characteristic impedance for obtaining the desired output current at CC charging phase is determined. And then, one of the resonant tank elements needs to be chosen and the other can be calculated from the value of \(R_0\). Mostly, a commercially available capacitor is selected and then the required value of the inductor is calculated. The resonance frequency is calculated as:

If the resonance frequency is not suitable for application, it can be adjusted by changing the values of the resonant tank elements. When a suitable capacitor value and resonance frequency is achieved, the required inductance value is calculated as follows:

Using these equations, the most crucial elements of the PRC are determined. The design steps explained in this section are briefly summarized as a flowchart in Fig. 8.

3.2.2 Choosing components

One big advantage of the SPA is that the peak voltage & current values of the resonant tank inductor & capacitor can be determined from the state plane trajectories given in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. If a solution for the steady state values of the PRC has already been obtained, the peak values can be easily determined using basic trigonometric principles. Since the details of the solutions can be found in [33] and [34], only the final solutions are given below. For the CCM case the peak component stresses are:

where \(M_{C_{rP}}\) and \(J_{L_{rP}}\) are the normalized peak capacitor voltage and inductor current values, \(\delta = \gamma -\beta\) (in DCM), \(J_{L_{r}}(0)\) and \(M_{C_{r}}(0)\) are shown in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. For the DCM case the peak component stresses can be expressed as:

Using (24) to (31) the components can now be determined.

3.3 Effect of transformer on resonant tank

A high frequency transformer is often employed in resonant converter applications for providing galvanic isolation and adjusting the voltage and current levels. Generally, the resonant tank is connected to the primary side of the transformer as shown in Fig. 9. Since the transformer introduces new elements to the resonant tank, it might be doubted whether a PRC can exhibit close to the ideal characteristics or not. In this section, the effect of transformer is investigated. A more detailed interpretation of the influence of the transformer can be found in [35].

Figure 9 illustrates the equivalent circuit of the resonant tank referred to the secondary side, where the transformer model is comprised of leakage and magnetizing inductances. As seen, the resonant tank now has more elements compared to the previously analyzed ideal case. In the ideal PRC, the resonant tank consists of two elements and the output rectifier of the PRC is driven with the voltage of the resonant capacitance, \(C_{r}\). On the other hand, the operation of the resonant tank might be influenced due to significant inductances introduced to the resonant tank circuit.

In order to prevent the transformer from influencing the operation of the PRC, there are two conditions that should be ensured. Firstly, the magnetizing inductance, \(L_{m}\), of the transformer must be relatively high compared to the resonant inductance, \(L_{r}\), so that the resonance frequency of \(L_{m}\) and \(C_{r}\) are very low compared to resonance frequency of PRC, \(w_{0}\). In this case, it can be assumed that almost no current is drawn by \(L_{m}\) at the operation frequency of PRC. Secondly, the leakage inductances, \(L_{p}\) and \(L_{s}\), must be very small compared to \(L_{r}\). However, it might be an impossible task to achieve a transformer design with high magnetizing inductance and very low leakage inductances. Therefore, it is probable that the operation of the PRC is influenced in this configuration, where the converter would actually act more like an LLC resonant converter.

For the facts mentioned above, it is proposed to connect the resonant tank to the secondary side of the transformer, as shown in Fig. 10. In this arrangement, the magnetizing inductance is again required to be relatively high so that it draws a minimum amount of current. Therefore, it can be assumed that all the current flowing through the leakage inductances is also flowing through the resonant inductor. Consequently, the magnetizing inductance can be neglected. With this assumption, it can be seen that the leakage inductances are connected in series with the resonant inductance and the output rectifier of the PRC is driven by the resonant capacitor voltage. This case is much more similar to the ideal case, when compared to the configuration given in Fig. 9. In fact, when the leakage and resonant inductance considered to act as a single inductor, the equivalent circuit is now same as the ideal case. Thus, the resonant tank is expected to operate in the same manner with the ideal case. Moreover, it can be seen that the leakage inductances also contribute to the resonant inductance. Consequently, the total value of the resonant inductance referred to the secondary side becomes:

It is also worth mentioning that the peak component stresses, given in (24) to (31), are now changed. The voltage values should be multiplied by n, whereas the current values should be divided by n.

4 Experimental verification

The principles of the proposed method are verified using two prototypes. While the first prototype does not involve a high frequency transformer, the second prototype is built to verify that the PRC with an high frequency transformer also operates in the same manner. Two prototypes, shown in Fig. 11, use the same circuitry with the exception of the resonant tank and transformer. Both setups aim to charge a 12 V – 7 A battery module, Yuasa NP7-12 lead-acid battery. Using the datasheets, the \(I_{\mathrm {max}}\) and \(V_{\mathrm {max}}\) values are determined to be 1.75 A and 14.7 V. According to the datasheet, the charging is completed when the current drops down to 0.5 A during CV phase.

It should be noted that, due to the parasitic resistances in the circuit, the output characteristics curves in Fig. 7 might be slightly deformed [36]. In this case, the curve at half resonance might not be a vertically straight line anymore. As the output current decreases, the voltage drops on the parasitic resistances decrease and consequently the output voltage slightly increases. Thus, the output voltage in the CV charging mode slightly increases as the power delivered to the battery decreases. Therefore, a transition voltage from CC to CV phase, \(V_{transition}<V_{\mathrm {max}}\), should be chosen considering the effects mentioned above. For the experimental setups \(V_{transition}\) is chosen to be 14 V.

The PRC is built by using half-bridge topology. A digital controller is used for producing PWM and detecting battery voltage to shift frequency from resonance frequency, to half-resonance frequency. Only using two PWM pins and a single ADC pin are enough for this proposed method. The battery voltage is measured by linear optocoupler in order to separate power ground and the controller.

The resonant inductance is wound by twisted litz wire. Therefore, eddy current effects such as the proximity effect and skin effect are minimized [37]. This inductance and the resonance capacitor have high ac voltage rating, low ESR and high dV/dt tolerance. The value of filter inductance is 0.8 mH, which is designed for half-resonance frequency. Thus, the size and losses of filter inductance might be relatively high. The design parameters of the experimental setups are calculated and shown in Table 3.

4.1 First experimental setup

The first setup does not involve a transformer for the sake of simplicity. Thus, it is considered that \(n=1\) and the input voltage is adjusted to be able to supply the desired output voltage. In spite of this fact, the idea is the same and the proposed technique can be confirmed.

\(I_{\mathrm {max}}\) and \(V_{\mathrm {max}}\) were previously chosen from battery data-sheet. Considering the voltage drops on the diodes (2 \(\times\) 0.74 V) and parasitic resistances (not much effective in this setup), \(V_{\mathrm {max}}\) is increased to be 16.2 V in order to ensure the maximum output of the converter to be 14.7 V.

The results for this setup are presented graphically in Fig. 12. It is observed that PRC operated very well in the CC charging mode, as the output current is accurately fixed to 1.75 A. In the CV charging phase, the output voltage value is increased from \(V_{transition}\) =14 V to \(V_{\mathrm {max}}\) =14.65 V while the output current decreased as predicted. The efficiency varies from 86% to 93%. The total charge transferred to the battery is nearly 4.95 A. The waveforms of resonant tank elements are presented in Fig. 13. The charger mainly stays within the CCM boundaries at CC mode, whereas it operates within the DCM boundaries at CV mode.

The soft switching feature of the PRC can be observed in Fig. 14, where the drain-to-source voltage of the MOSFET and current of the resonant inductor illustrated. As it can be seen, while ZVS turn-on can be observed in both CC and CV charging modes, ZCS turn-off can be observed in later phases of CV charging mode as the output current decreases. Lastly, the output waveforms of the circuit during the transition from CC to CV mode are presented in Fig. 14d, where the CH2 signal denotes the time that the switching frequency is changed from resonance frequency, \(\omega _0\), to half resonance frequency \(\omega _0/2\). As shown in Fig. 14d, a very smooth transition from CC to CV charging is achieved.

The most of the losses are caused by the diodes of the output rectifier. As an LC filter is employed at the output, the diodes are always conducting. Moreover, the voltage drops on the diodes are constant and they are significant in applications with low voltage output. Thus, although the efficiency values are good, they can improve remarkably if the uncontrolled output rectifier is replaced by a synchronous rectifier circuit at the output, especially for low voltage applications.

As it can be seen from the results, the voltage in CV phase slightly increased, as the quality factor \(Q=R/R_{0}\) rapidly changes. This is due to parasitic resistance in the circuit, which are mostly caused by inductances (resonant inductance and filter inductance). However, despite the fact that charging voltage increased in CV phase, the charger was able to gradually decrease the charging current as required.

4.2 Second experimental setup with transformer

For the DC-DC converters, high frequency transformers are of major importance since they ensure isolation and ability to change voltage and current levels. The second prototype is built in order to confirm whether the PRC exhibits same characteristics when a high frequency transformer is included.

The second experimental setup is presented in two versions. In the first version, no feedback controller is implemented. On the other hand, the second version includes a feedback controller with hysteresis control algorithm, which is utilized only in CV charging phase, so that a more strict CV phase can be achieved.

For this setup a transformer with a turns ratio of \(n=40/45\) is wound. The transformer has the following parameters; \(L_{p}=6.38 \,\, {\mathrm {\upmu H}}\), \(L_{s}=5.12 \,\, {\mathrm {\upmu H}}\) and \(L_{m} = 266\,\, \mathrm {\upmu H}\). Considering the additional voltage drops across parasitic resistances of transformer (nearly 0.3 \(\mathrm {\Omega }\)) will cause the output values to decrease, \(V_{\mathrm {max}}\) is increased to 16.45 V and \(I_{\mathrm {max}}\) is chosen to be 1.80 A due to fact that these resistances cause a decrease of the output current. Since a transformer with a predetermined turns ratio is utilized, the input voltage of the PRC is adjusted according to (17). Using the predetermined values the design parameters are calculated as in Table 3.

4.2.1 Open loop operation

The results of this test are illustrated in Fig. 15. It can be seen that PRC operated again very well in the CC charging mode, as the output current is accurately fixed to 1.74 A. However, in the CV charging phase, the output voltage value is increased from \(V_{transition}= 14\hbox { V}\) to \(V_{\mathrm {max}}=14.73\hbox { V}\). Despite this fact, the circuit was able to decrease the output current as predicted. The efficiency varies between 78% and 88%. The charger mainly stays within the CCM boundaries at CC mode, whereas it mainly operates within the DCM boundaries at CV mode, as seen in Fig 16. The total charge transferred to the battery is nearly 4.55 A.

The reason for the less efficiency values are due to the losses in the transformer. The calculated resistance of the transformer are considerably high. It is observed that the transformer caused a nearly 8% drop in the efficiency. The PRC in the second experiment also have more voltage increase in CV phase. This is again caused by the extra parasitic resistances introduced to the circuit by the transformer. In spite of that, the charger again achieved to decrease the charging current. For ensuring isolation with higher efficiency values, the operating frequency should be increased. This will decrease the sizes of the inductors, capacitors and transformer, which will also reduce the resistances introduced by these elements. Thus, the PRC can operate closer to the ideal characteristics at higher switching frequencies (also valid for the first setup as well).

4.2.2 Utilizing controller for CV charging phase

In the previous setups it has been demonstrated that the proposed battery charger does not need any controller at CC charging phase, as the current supplied at resonance frequency remained constant. On the other hand, there is a voltage increase in CV charging phase, as explained previously. Although the converter does not exceed the predefined maximum charging voltage, a more strict CV charging phase might be required for some applications. Thus, it is aimed to represent such a case by incorporating a controller to adjust the switching frequency of the converter to near half resonance frequency in order to supply a constant charging voltage in CV phase. For this purpose, a hysteresis control algorithm is implemented while the rest of the experimental setup remains the same. For this case, a transition voltage is not necessary, so that the transition from CC to CV phase will occur when the battery voltage is equal to 14.7 V. Afterwards, the implemented algorithm will keep the voltage around 14.7 V for the rest of the CV charging period. The results are shown at Fig. 17. The total charge transferred to the battery is nearly 4.49 A.

The results show that the controller was able to achieve a constant voltage output at CV charging phase by adjusting the switching frequency from 22.434 kHz to 20.192 kHz. The regulation of the switching frequency is nearly 2.25% of the resonance frequency, which is quite small.

5 Conclusion

In this study, a simple design and control approach for CC-CV charging application of PRC was presented. The PRC was operated at two different frequencies, which are \(F=1.0\) and \(F=0.5\), as CCS and CVS, respectively. Thus, the need for closed-loop controllers with the purpose of output current and voltage regulation were eliminated. The electrical design of the charger and implementation procedure were simplified. The output filter design was also simplified due to the constant frequency operation. Sharp changes of switching frequency, which is claimed to decrease the overall efficiency, are avoided. The number of required components and related costs were decreased. What is more, the operation of the PRC at half resonance frequency inherently constitutes an output voltage limitation at no load condition. Furthermore, the poor performance of the PRC in CV charging phase, as claimed by the study [18], was also avoided by operating the PRC at half resonance frequency, in DCM.

The performance of the proposed circuit is evaluated with two experimental setups. It is shown that the designed prototypes operate at reasonably good efficiency values: the first setup achieves efficiency values between 86% and 93%, while the efficiency values of the second setup are found to be in the range of 78%-88%. Moreover, it is also shown in Fig. 14d that the transition from CC to CV charging do not result in any kind of oscillations.

The results approve the validity of the proposed method, as the designed chargers are able to operate without closed loop controllers for a wide range of load values in both CC and CV charging phases. The designed chargers are able to supply a constant current output, which are well fixed to nearly 1.75 A. It is shown that high parasitic resistances in the circuit affects the performance especially in CV phase, where a nearly 0.7 V increase is observed. Despite this fact, the proposed charger is able to reduce the charging current to 0.5 A in CV phase, as desired.

Although the results are quite good, an experimental setup with a controller at CV phase is also presented for comparison with open-loop operation. In this setup it is shown that the converter is able to assure a constant output voltage with a little amount of frequency adjustment, which corresponds to a change of nearly 2.25% of the resonance frequency.

On the other hand, precautions must be taken in the design process, since the proposed charger requires input voltage stability for achieving constant voltage/current output, when no controller is employed. Moreover, the values of resonant tank elements, \(L_r\) and \(C_r\), have a direct effect on the output current value in CC phase. Additionally, the voltage increase in CV phase is caused by the parasitic resistances in the circuit. The CV tracking performance of the circuit can be improved by increasing the resonance frequency of the converter for decreasing the sizes of magnetic elements and their parasitic resistances.

The major loss mechanism of the presented low voltage output experiments are caused by the voltage drops on the rectifier diodes. This is due to fact that the diode voltage drops are relatively large in low voltage output charger circuit. Thus, employing a synchronous rectifier circuit at the output would increase the overall efficiency. In contrast to low voltage chargers, the diode voltage drops are not a big concern for high voltage charger applications, where the efficiency of the proposed charger circuit is expected to increase dramatically.

References

Chuang YC, Ke YL, Chang SY (2009) Highly-efficient battery chargers with parallel-loaded resonant converters. In: Proceedings of IEEE industry applications society annual meeting, Houston, USA, 4–8 October 2009, 10 pp

Schalkwijk WAV, Scrosati B (2002) Advances in lithium-ion batteries. Springer, Germany

Rand DAJ, Moseley P, Jürgen GCP (2004) Charging techniques for VRLA batteries. Elsevier, Holland

Chuang YC, Chuang HS, Liao YH et al (2014) A novel battery charger circuit with an improved parallel-loaded resonant converter for rechargeable batteries in mobile power applications. In: Proceedings of IEEE 23rd international symposium on industrial electronics, Istanbul, Turkey, 1–4 June 2014, 7 pp

Chuang YC, Ke YL, Chuang HS et al (2011) Analysis and implementation of half-bridge series parallel resonant converter for battery chargers. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 47(1):258–270

Chandrasekhar P, Reddy SR (2009) Analysis and design of embedded controlled parallel resonant converter. Annals of Dunarea De Jos 32(1):24–29

Chuang YC, Ke YL (2007) A novel high-efficiency battery charger with a buck zero-voltage-switching resonant converter. IEEE Trans Energy Convers 22(4):848–854

Deng J, Li S, Hu S et al (2014) Design methodology of LLC resonant converters for electric vehicle battery chargers. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 63(4):1581–1592

Gu B, Lin CY, Chen B et al (2013) Zero-voltage-switching PWM resonant full-bridge converter with minimized circulating losses and minimal voltage stresses of bridge rectifiers for electric vehicle battery chargers. IEEE Trans Power Electron 28(10):4657–4667

Hu S, Deng J, Mi C et al (2014) Optimal design of line level control resonant converters in plugin hybrid electric vehicle battery chargers. IET Electr Syst Transp 4(1):21–28

Han HG, Choi YJ, Choi SY et al (2016) A high efficiency LLC resonant converter with wide ranged output voltage using adaptive turn ratio scheme for a Li-ion battery charger. In: Proceedings of 2016 IEEE vehicle power and propulsion conference, Hangzhou, China, 17–20 October 2016, 6 pp

He P, Khaligh A (2016) Design of 1 kW bidirectional half-bridge CLLC converter for electric vehicle charging systems. In: Proceedings of 2016 IEEE international conference on power electronics, drives and energy systems, Trivandrum, India, 14–17 December 2016, 6 pp

Lee YS, Han BM, Lee JY et al (2013) New three-phase on-board battery charger without electrolytic capacitor for PHEV application. In: Proceedings of 28th annual IEEE applied power electronics conference and exposition, Long Beach, USA, 17–21 March 2013, 6 pp

Kang YG, Upadhyay A (1988) Analysis and design of a half-bridge parallel resonant converter. IEEE Trans Power Electron 3(3):254–265

Kang YG, Upadhyay A, Stephens D (1991) Analysis and design of a half-bridge parallel resonant converter operating above resonance. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 27(2):386–395

Chen W, Wu X, Yao L et al (2015) A step-up resonant converter for grid-connected renewable energy sources. IEEE Trans Power Electron 30(6):3017–3029

Wu X, Chen W, Hu R et al (2014) A transformerless step-up resonant converter for grid-connected renewable energy sources. In: Proceedings of IEEE energy conversion congress and exposition, Pittsburgh, USA, 14–18 September 2014, 6 pp

Wang H, Khaligh A (2013) Comprehensive topological analyses of isolated resonant converters in PEV battery charging applications. In: Proceedings of transportation electrification conference and expo, Detroit, USA, 16–19 June 2013, 7 pp

Alonso J, Perdigão M, Vaquero D et al (2012) Analysis, design, and experimentation on constant-frequency dc-dc resonant converters with magnetic control. IEEE Trans Power Electron 27(3):1369–1382

Ryu SH, Kim DH, Kim MJ et al (2014) Adjustable frequency-duty-cycle hybrid control strategy for full-bridge series resonant converters in electric vehicle chargers. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 61(10):5354–5362

Dananjayan P, ShRam V, Chellamuthu C (1998) A flyback constant frequency ZCS-ZVS quasi-resonant converter. Microelectron J 29(8):495–504

Pitel I (1986) Phase-modulated resonant power conversion techniques for high-frequency link inverters. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 22(6):1044–1051

Tsai FS, Materu P, Lee FC (1987) Constant-frequency, clamped-mode resonant converters. In: Proceedings of power electronics specialists conference, Blacksburg, USA, 21–26 June 1987, 10 pp

Tsai FS, Sabate J, Lee F (1989) Constant-frequency, zero-voltage-switched, clamped-mode parallel resonant converter. In: Proceedings of telecommunications energy conference, Florence, Italy, 15–18 October 1989, 7 pp

Falco GD, Gargiulo M, Breglio G et al (2012) Design of a parallel resonant converter as a constant current source with microcontroller-based output current regulation control. In: Proceedings of power electronics, electrical drives, automation and motion, Sorrento, Italy, 20–22 June 2012, 4 pp

Chung S, Kang B, Kim M (2013) Constant frequency control of LLC resonant converter using switched capacitor. Electron Lett 49(24):1556–1558

Lee BK, Kim JP, Kim SG et al (2016) A PWM SRT dc/dc converter for 6.6-kw EV onboard charger. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 63(2):894–902

Valipour M, Banihabib ME, Behbahani SMR (2013) Comparison of the ARMA, ARIMA, and the autoregressive artificial neural network models in forecasting the monthly inflow of Dez dam reservoir. J Hydrol 476:433–441

Giri F, Maguiri OE, Fadil HE et al (2011) Nonlinear adaptive output feedback control of series resonant dc-dc converters. Control Eng Pract 19(10):1238–1251

Elmaguiri O, Giri F, Fadil HE et al (2009) Adaptive control of a class of resonant dc-to-dc converters. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 42(9):290–295

Gücin TN, Biberoglu M, Fincan B (2015) A constant current constant-voltage charging based control and design approach for the parallel resonant converter. In: Proceedings of 2015 international conference on renewable energy research and applications, Palermo, Italy, 22–25 November 2015, 6 pp

Bucher A, Durbaum T, Kubrich D et al (2006) Comparison of different design methods for the parallel resonant converter. In: Proceedings of power electronics and motion control conference, Portoroz, Slovenia, 30 August–1 September 2006, 5 pp

Johnson S, Erickson R (1988) Steady-state analysis and design of the parallel resonant converter. IEEE Trans Power Electron 3(1):93–104

Oruganti R, Lee FC (1985) State-plane analysis of parallel resonant converter. In: Proceedings of power electronics specialists conference, Toulouse, France, 24–28 June 1985, 8 pp

Biberoglu M, Gucin TN, Fincan B (2016) Analyzing the influences of high frequency transformers utilized in parallel resonant converters. In: Proceedings of 2016 IEEE international conference on renewable energy research and applications, Birmingham, UK, 20–23 November 2016, 6 pp

Fincan B, Gucin TN, Biberoglu M (2016) Extending the state plane analysis of parallel resonant converter by incorporating several non-ideality sources. In: Proceedings of 2016 18th European conference on power electronics and applications, Karlsruhe, Germany, 5–9 September 2016, 11 pp

Fincan B, Ustun O (2014) A study on solutions for wireless energy transfer limitations. In: Proceedings of 7th IET international conference on power electronics, machines and drives, Manchester, UK, 8–10 April 2014, 6 pp

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

CrossCheck date: 5 March 2018

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

GÜCIN, T.N., BIBEROĞLU, M. & FINCAN, B. Constant frequency operation of parallel resonant converter for constant-current constant-voltage battery charger applications. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 7, 186–199 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-018-0403-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-018-0403-7